EMILIANO ZAPATA: HERO IN HISTORY AND ART

My good friend Jim Baird wrote this essay as a contribution to this web site. It all started one day several months ago when I asked him what his favorite movie was. The answer: Viva Zapata! And no hesitation. I didn’t know it then, but none other than John Steinbeck wrote the screenplay and Marlon Brando played the title role. Other actors that even I knew included Anthony Quinn and Jean Peters. That’s when my interest in Zapata begun. Read on: a fascinating man and a fascinating life, as well as a great movie.

When

the Indian peasants of the Mexican state of Chiapas began a revolt against the

national government in the Fall of 1993, they called themselves zapatistas. This designation honors Emiliano Zapata

(1879-1919), the most revered leader of the Mexican Revolution of

1910-1919. The peasants’ demand that

they be allowed to hold their own land and control their own destinies echoed

Zapata’s simple goals for the poor people of his time. Zapata’s aims were easy to understand but

their fulfillment most difficult, a point which Zapata understood when he began

to fight for freedom in 1909, even before the historically recognized beginning

of the Revolution in 1910, when Francisco Madero openly challenged the official

government. Zapata was able to attract

the love and loyalty of unlettered peasants, yet intelligent and crafty enough

to keep fighting the Revolution for ten years, after other leaders had been

killed or had betrayed its goals. His

death in an ambush in 1919 galvanized his followers against the government

which had engineered his murder and helped to bring about the completion of the

revolution.

Such a figure is fascinating for a number of reasons, and the story of his life begs for dramatic presentation. In 1952, Twentieth Century-Fox released Viva Zapata!, a film with high-powered talent behind it. John Steinbeck wrote the screenplay, Darryl Zanuck produced the film, Elia Kazan directed, Marlon Brando played the title role, and other actors included Anthony Quinn, Jean Peters, Joseph Wiseman, Alan Reed, Harold Gordon, and Mildred Dunnock. Obviously, when a film is based on the life of a historical person, it is fair to ask if the film correctly presents the facts of that person’s life. This paper will maintain that although the film contains many flaws, including misrepresentation of some of the details of Zapata’s life, it is nonetheless successful in presenting what was most true and valuable about this remarkable person.

Before examining the Viva Zapata!, it is necessary to sketch briefly the events of the Mexican Revolution which is its background. The country had suffered for thirty four years under the dictatorial regime of “President for life” Porfirio Diaz. Not all had suffered, of course. In the pattern of most Latin American countries, a small ruling class held most of the wealth while the peasants did most of the work. Conditions had worsened in the years before 1910 because of the rapid expansion, with the blessings of the Diaz regime, of the hacienda system. The haciendas were huge farms in the state of Morelos which grew sugar, a cash export crop. In order to increase their profits, the hacienda owners expropriated from the peasants land which they had held for hundreds of years. The peasants, unable to grow their survival crops such as corn, grew restive and finally desperate.

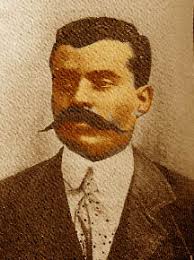

Emiliano Zapata lived in Morelos, small (about the size of a large American county) but very important because of its agricultural wealth, large capital city, Cuernavaca, and proximity to the national capital, Mexico City, which is only about twenty miles from Morelos’ northern border. Zapata, a mestizo (person of mixed European and Indian ancestry) was born in 1879 to the owner of a small rancho. Upon Zapata’s father’s death when Emiliano was eighteen, he took over ownership and personal operation of the rancho and prospered. Thus he was not poor, but not wealthy either. This position made it easy for other peasants to identify with him in the early days of the Revolution, before events caught him up and he became primarily a military and political leader. He was what they wanted to be: a farmer who was successful through the work of his own hands, but not an exploiter of others. When the haciendas began to encroach on the peasant lands, the people turned naturally to Zapata for leadership and he organized several successful seizures of hacienda land to return that land to the villages which originally owned it.

The problems of the Morelos peasants became national concerns when Francisco Madero of the northern state of Coahuila started the Mexican Revolution by announcing the “Plan of San Luis Potosi” which called for open elections and constitutional government along with land reform. Local leaders raised armies all over Mexico to oppose Diaz, who was so thoroughly hated that this phase of the Revolution went easily–too easily, as it turned out–and Diaz was driven to exile in Paris in 1911, strongly motivated by the capture of the city of Cuautla in Morelos by Zapata’s guerilla army.

Madero was the leader of the new provisional government, although Francisco Leon de la Barra, former ambassador to the United States, became interim president. The faults of the bookish Madero were quickly evident. A fair and reasonable man, he expected the same qualities in all with whom he dealt once the evil Diaz had been ousted. Madero placed great faith in the legal system and did not see that many of his allies did not believe in the goals of the revolution but were merely using the turmoil as a chance for their own advancement. Madero disliked violence and thought it would not be necessary with Diaz gone, so that when he finally had to order attacks, the resentment against him grew because his former pacificism was then viewed as hypocrisy. With the federal army and the hacienda system still intact, Zapata and his troops were reluctant to give up their arms. Their fears were proven well founded when de la Barra ordered General Victoriano Huerta to attack Zapata’s forces.

Although Madero became president near the end of 1911, he became more ineffectual as Huerta grew stronger. Shortly after Madero’s assumption of the presidency, Zapata announced his allegiance to the “Plan of Ayala” which reaffirmed the land reform goals of the original revolution. Zapata and his “men of the south” continued to fight against increasingly brutal attacks on Morelos by federal troops. Meanwhile, in February 1913, Huerta engineered a coup against Madero, probably had him assassinated, and assumed dictatorial powers which reinforced the pre-revolution economic, social, and political forces. Huerta’s harsh regime brought about a reaction from the Constitutionalists of the north led by Venustiano Carranza. Their main military arm, commanded by Pancho Villa, defeated the federal forces in two battles at the northern city of Torreon. Huerta, threatened by Villa in the north and Zapata in the south, fled the country in July 1914.

Carranza assumed power, but his Constitutionalists were split. A convention was held at Aguascalientes to resolve the differences between the factions. The Villa wing demanded more land reform, as did Zapata’s adherents. Carranza announced his opposition to the Plan of Ayala, and the fighting continued. Carranza and the Constitutionalists were driven to Vera Cruz, and Villa and Zapata triumphantly occupied Mexico City in November 1914. The Constitutionalists took advantage of the continued disarray in the revolutionary ranks to move out of Vera Cruz under the command of General Alvaro Obregon in January 1915 and defeat Villa in a series of encounters.

With Villa neutralized in the north, the burden of carrying on the fighting fell largely to Zapata. Villa had made a fatal error for a lightly equipped guerilla fighter; he engaged a superior force (which had artillery and machine guns) in a pitched battle. Zapata never knowingly squandered his resources in such a way. As a result, he was able to fight on against increasingly violent attacks by the Carranza regime which devastated Morelos and nearby states.

Hoping to obtain more supplies, arms, and troops for his struggle, Zapata was led into a trap by Carranza’s forces, ambushed and killed in April 1919. Zapata’s death further galvanized his followers to fight on, and the next year, when Obregon drove Carranza from power, the zapatistas made peace with Obregon, ending the fighting of the revolution.

The makers of a two hour film could not expect even to present all these events, much less comment upon them accurately. Nonetheless, Viva Zapata! hits the high spots well. The film shows Diaz’s oppression, the rebellion against it, Diaz’s fall, Madero’s ineptitude, Huerta’s villainy and the murder of Madero, and Villa’s and Zapata’s triumphal joint occupation of the capital as Huerta is driven out. The film departs from fact by showing Zapata as President, an office he never held, but this distortion is made for important dramatic reasons, as will be shown below. The facts of Zapata’s ambush and killing are close to the real historical events, but the film does not end with the establishment of a peaceful government but with the dumping of Zapata’s body on a town square, another real historical event.

The Iliad, which purports to be the story of the Trojan War, does not end with the defeat of the Trojans but with the funeral games for Hector. The real story of the Iliad is the change in the character of Achilles from an arrogant bully to a murderous bastard and finally into an understanding and sympathetic human being. The story which brings an audience to the theater to watch Viva Zapata! is the epic struggle of the Mexican people’s fight for freedom, but what they see instead is the development of a great man’s ideas and character and his attempt to impart what he has learned to his people.

The film’s Zapata does not change his principles at all. He appears in the first scene of the film as part of a delegation to Diaz who ask that their president return to them their ancestral lands taken from them by the haciendas. Diaz stalls them; Zapata steps forward and says that they haven’t time for delay because the corn must be planted now. Irritated, Diaz asks Zapata his name and ominously circles it on the delegation list. (It also appears circled in the opening credits, emphasizing Zapata’s status as a marked man.) Thus in the first scene Zapata appears as a man who not only recognizes injustice but strongly opposes it. The historical Zapata never forgot where he came from and what he was fighting for; he stopped or slowed his military campaigns so that his agrarian soldiers could tend their crops at planting and harvest times. This viewpoint remains intact. At the end of the film, when he rides off to seize ammunition and arms and his wife tries to prevent him from going into what she correctly suspects is an ambush, all he can say is, “I must do what’s needed” (Steinbeck 113).

After the scene with Diaz, the film’s Zapata, in attempt to improve his position and thereby impress the father of the girl he is courting, works as a horse trainer for a wealthy landowner. He sees a peasant boy eating from a horse trough and turns away in disgust. When another trainer beats the boy for “stealing food”, Zapata explodes with rage and attacks the trainer. When he is pulled off him, all he can do is to justify his actions is say angrily, “That boy was hungry. . . . He was hungry” (Steinbeck, 29). Viva Zapata! was the first film Marlon Brando made after the movie version of A Streetcar Named Desire (1951). In both his most famous role as Stanley Kowalski and as Zapata, Brando’s strong suit was his ability to convey a sense of barely suppressed rage which suddenly erupts into violence. In Stanley, this explosion is frightening and disheartening. In Zapata, it is inspiring and uplifting, as his own sense of what is right triumphs over his calculations for personal advancement.

Actually, the historical Zapata went through no such machinations. He was married to his wife, Josefa, long before the revolution began. He is seen as being interested only in his future wife, when the real Zapata had several other lovers and a number of children out of wedlock. In the film, Josefa’s father first objects to the match because of Zapata’s lower social status, then allows the marriage when he sees Zapata’s power, and finally hangs around to complain when the struggle goes badly. In fact, Zapata’s father-in-law died before the revolution began. The part of the film involving Zapata’s romance and marriage are a major subplot, but it seems to be there in order to provide a female lead in what would be otherwise an all-male cast, an element which was assumed at the time to repel audiences. Perhaps the low point in the Hollywood treatment of Zapata’s marriage occurs when Emiliano confesses to Josefa on their wedding night that he can’t read and she begins to teach him.

That scene leads directly to the meeting between Zapata and Villa in Mexico City. After posing for a photograph (This scene exactly copies an historical picture.), the two men loll on the grass near a lake and discuss the future. Villa asks Zapata, “Can you read?” When Zapata says he can, Villa replies, “You’re the president” (Steinbeck, 95). In fact, Zapata was not only literate, but an excellent user of language, as his revolutionary manifestoes and battle orders show.

This scene is an example of one of the film’s main weaknesses, which is a tendency, in spite of a sympathetic viewpoint, to present Mexicans as rather ignorant though good-hearted churls and therefore figures of fun. In a scene after a successful battle, Zapata receives gifts of food, liquor, and livestock from his grateful people. He stands to accept their praise with the legs of a squealing pig in one fist and two struggling chickens in the other while rifles and pistols are fired in the air and people scream. This scene always provokes laughter in an audience, and its bias may be traced, unfortunately, to John Steinbeck’s screenplay. Steinbeck loved Mexico and frequently used that country as the locale of his works (Sea of Cortez, The Pearl) or used chicano characters (“Flight”, Tortilla Flat), and he interviewed men who had actually fought with Zapata in preparation for writing the screenplay, but he seemed not to be able to avoid a patronizing attitude toward latinos.

A related problem is the use of anglo actors in a film about the Mexican Revolution. Anthony Quinn, who played Zapata’s brother Eufemio, is of Mexican and Irish ancestry; every other actor in the cast is an anglo made up to look Mexican. But considering who was paying for the film, the casting could hardly have been otherwise. Also, with the lead played by Brando at the height of his powers, it is hard to imagine that anyone else could have done better.

Some of the changes to the figure of Zapata seem to worsen his image so that the film is not just patronizing but distorting. For example, Zapata personally executes a longtime associate whose loose talk has cost his army a victory. The historical Zapata never did anything like this. He used force as much as was needed to accomplish his goals, but no more. Although stories were spread about him both during and after the revolution, and a book written to discredit him as a savage (The Crimson Jester), Zapata issues orders that his troops were to behave as gentlemen after they had conquered an area. He could not prevent atrocities, but he did not condone them.

In dramatic terms, the scene in which Zapata kills his comrade is there to underscore one of the most important points raised by the film, which is that the revolution is never over and that the pressures on a moral person and leader such as Zapata finally become immense. The fight against Diaz is over about thirty minutes into the film, surprising both revolutionaries and audience, who think that the conflict in which they have been immersed is over. Instead, both revolutionaries and audience find that there are always new challenges to a civility–trusted friends become traitors, goals announced in war are hard to realize in peace, and the moral person himself becomes corrupted. The presentation of these increasing difficulties is the purpose of the historically inaccurate scene in which Zapata as president of Mexico, an office he never held, receives a group of farmers with a grievance against Zapata’s brother Eufemio, who has killed a man and taken another man’s wife in the course of seizing a hacienda he wanted. Zapata says he will look into the matter but one man insists that this is not enough. Angered, Zapata asks for his name and circles it on the delegation list. Then he realizes that he is doing exactly what Diaz did to him, and he leaves Mexico City to confront his brother.

The scene which follows is the key scene in the film. Eufemio points out that the enemies they defeated are living in comfort while he has nothing, and he is going to act as a conqueror and take what he wants. Zapata, recognizing that both he and his brother can not match the ideals of the leader the people want. He addresses his people: “You look for leaders. Strong men without any faults. There aren’t any. There are only men like yourself. They change. They desert. They die. There’s no leader but yourself. A strong people is the only lasting strength” (Viva Zapata! sound track).

There is an important difference between the screenplay and the sound track in this scene. In the screenplay, Zapata says, just before he says that a strong people is the only lasting strength, he says “I will die, but before I do I must teach you that a strong people is the only lasting strength.” It has been suggested that Zapata knew that he was going to be ambushed and accepted his death as a means of unifying his people and giving them the strength to continue the revolution. They relied upon him too much. If he is not there, they must rely on themselves. The film shies away from making this Christ-like gesture explicit, though the similarity is strongly hinted at in the final scene, in which Zapata’s body is dumped on a town square in a crucifix pose while well water runs from a pipe beneath his body. The assembled villagers refuse to accept the mutilated body as that of Zapata, claiming that “He’s in the mountains. You couldn’t find him now. But if we ever need him again–he’ll be back” (Steinbeck 122).

Viva Zapata! demonstrates in dramatic terms that the high-mindedness of Madero is useless without the force of Huerta, but applied with judgment and restraint. The actual Emiliano Zapata was even more remarkable than the hero of the film, combining these qualities in real life. Perhaps his only flaw was his refusal of the power of the Mexican presidency when it came to him. He understood correctly that “a strong people is the only lasting strength”, but they do need someone to show them how to be strong. The Mexican people, faced with confusion and duplicity on all sides, needed a really courageous and wise leader. They needed him. It is true that there are no strong men without any faults, but some people are more what we should be than others.

Works Cited

Dunn, H. H. The Crimson Jester: Zapata of Mexico. New York: Robert M. McBride, 1933.

Millon, Robert P. Zapata: The Ideology of a Peasant Revolutionary. New York: International Publishers, 1969.

Parkinson, Roger. Zapata. New York: Stein and Day, 1975.

Steinbeck, John. Viva Zapata!: The Original Screenplay by John Steinbeck. Edited by Robert E. Morsberger. New York: Viking Press, 1975.

Womack, John Jr. Zapata and the Mexican Revolution. New York: Knopf, 1969.

9 thoughts on “Emiliano Zapata.”

It’s an amazing article designed for all the web viewers; they will get

benefit from it I am sure.

As a Newbie, I am continuously browsing online for articles that can benefit me. Thank you!

At this time I am ready to do my breakfast, after having my breakfast coming again to read other news.|

Incredible points. Sound arguments. Keep up the great work.

Awesome blog, thanks for the useful information.

Wow, wonderful blog layout! How long have you been blogging for? you make blogging look easy. The overall look of your website is fantastic, as well as the content!

I need to to thank you for this excellent read!! I absolutely enjoyed every little bit of it. I have you book-marked to look at new things you post…|

When someone writes an piece of writing he/she retains the image of a user in his/her brain that how a user can know it. Thus that’s why this article is amazing. Thanks!|

Aw, this was an extremely good post. Taking a few minutes and actual effort to make a very good article… but what can I say… I put things off a whole lot and don’t seem to get nearly anything done.|

Comments are closed.