Some people are different, that’s all there is to it. Time, place and circumstances made them that way and I’ve had the fortune to meet some. Antonio, the character is this story is one of them. His name in real life is actually Antonio, same as in the story, and in this excerpt, same as in the book – as yet unnamed – he’s a central figure where the background is Tierra del Fuego. The book is undergoing the review process prior to being published and I’m thinking of going with audio first.

m

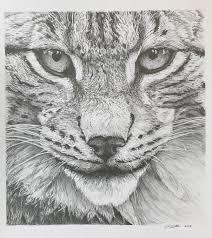

~ A different type of cat ~

The fact that we had people walking around our estancia was troubling, and I saw no reason for them to do so, unless they were up to no good. Recently, Antonio had taken me to a spot where four men had died from exposure. They had backpacks full of drugs and were well armed, but there was no signs of a struggle, or any indication of what could have happened to them, or what happened to the drugs and arms they were surely carrying, except for the mostly empty backpacks and tons of ammunition scattered about. Anyone could tell that a lot of what they had carried was missing, but, other than their own footprints, there were no other tracks. This had bothered me for a whole week now, and figure as I might, I was no closer to a clue. The police had gone out and taken a look, but they were city police, best suited for directing traffic at a busy intersection when the lights go out. They had no idea what to do when they got there, and same as me, were basically lost in the backcountry. And not only lost, but wet, soaked to the bone and freezing. So, to get an answer, or perhaps some insight, I went to see my friend Antonio, who had found the men in the first place. As always, he was expecting me, although I had gone there on the spur of the moment, unannounced. How he managed that, was another unknown.

I must have been anxious because no sooner had a greeted him that morning than I started asking questions. “Who are these people, Antonio? What do they want?”

With Antonio, being in a hurry was a mistake. It only meant you were going to have to wait. The bigger the hurry, the longer the wait. I knew that, but still, I rushed right in with the questions. On the other hand, being calm and collected was no different, and also carried consequences. Mainly, it was like waiving a red flag at a Spanish bull: Antonio was not indifferent, any more than those bulls, meaning that if you came to see him all calm and collected, like a cool as a cucumber matador, most of the time you ended up having to run and head for the fence.

My friend Antonio was, in three words, a different story. I never thought I would really love a man, but without meaning to, I knew I loved this one. It was hard not to. He was such a different type of cat, it was impossible not to like him at first, then you naturally came to love the guy, he gave you no choice. Living alone in the middle of a 20,000 acre estancia in Tierra del Fuego was no easy thing, but he not only lived, he flourished. He and his wife María, that is, let’s not forget her. María was the person that made the homemade butter and the wonderful bread I could smell baking in their wood burning stove. Suddenly, I was in a hurry again, wishing she would hurry, as waiting for the expected basket-full of steaming hot bread and fresh brewed coffee was becoming a minor torture. I think that if I’m ever forced to choose a one and only food, I will choose hot, homemade bread and María’s homemade butter. Early mornings, mid mornings, anytime, nothing can beat it. And I don’t mean regular hot bread, but steaming hot, seconds out of the oven: bread you have to spear with a fork or blister two fingers.

María was Antonio’s metaphorical rock, and if a person needed one, a better, more solid rock would be hard to find. I had never seen two people better suited to each other than these two, and I admit, it was hard to think of one without the other. Still, two people adrift in a vast ocean of nothing but space was, in my mind, the same as being alone. Living solo in the immense expanse of sea, air and land that was Tierra del Fuego was not for everybody: a land forgotten by time, but not by the elements, or its wildlife, and because of its remoteness, bypassed by anybody with any sense. But what did I know? My name is Segundino, a recent arrival from Europe and new here. Antonio and his people, on the other hand, had been here for generations, same as María.

By now I was also convinced that he was one of those deep thinkers that always bears watching. The kind of guy that admits to nothing but seems to know everything. The innocent grandpa type that looks distracted while playing chess, because at the time, he is distracted. He’s not paying attention to the game because he doesn’t have to. He’s thinking of something else, or busy sharpening his Bowie style knife to a razor’s edge, as thrashing you requires no effort. At his age, the tendency for most people is to be static, as opposed to dynamic, to stick to the obvious and the mundane, and to have a routine, as opposed to live the unexpected. And there is a reason for that: unless you are fit, when the unexpected does happen, if it’s of sufficient import, most people flounder at best and perish at worst. But not Antonio. I believe he saw himself as fit and adaptable, a man trained by life and circumstance to cope with anything and afraid of nothing. I, on the other hand, saw him as extremely unpredictable, so much so, I was always alert with him around. This time was no different, as he chose not to answer my questions at all, but rather asked me another one instead ‒ no problem there, I was getting used to him.

“Seg,” he started. “What do you think was man’s worst invention?”

I knew the answer to my question was somehow wrapped inside of his, like a small enigma hides inside a big conundrum, but for the life of me I couldn’t figure out how or where. I thought about it.

“DDT? TNT? Emojis? Plastic grocery bags? Bottled water? Subprime mortgages?”

He laughed. “Maybe I should have said worst discovery, not necessarily an invention as such.”

After a prolonged silence, in which I came up blank, I admitted to not having a clue.

“To me,” he said in all seriousness, “man’s worst discovery was agriculture.” He then went on to explain.

“Remember those inlets and coves I mentioned earlier, the ones where the tracks I had been following disappeared? At low tide, there are so many slugs, shrimp, crabs and seaweed, on top of shellfish like scallops, mussels, oysters and clams, all visible on the exposed ocean floor that I think a group of fifty hunter gatherers could live within sight of those inlets and never go hungry, ever. Then there is a seal colony within twenty minutes walking distance, and nothing but eggs of one variety or another all the way there and back. Literally tens of thousands of eggs laying on the ground for easy pickings and at least fifty thousand seals dying to provide you with their skins and blubber. And that’s all within a few miles walk. I think the original inhabitants of these lands, such as the Onas, or Alacalufs, did not get here by accident or because they were chased away from other lands, but came here because they hated agriculture and wanted nothing to do with it. As you know, traditional agriculture in Tierra del Fuego is out of the question.

“Think about it,” he continued. “Imagine our primitive farmer getting up at the break of dawn to cut trees and remove the stumps before he can work the fields. He does that tiring back-breaking task every day from dawn to dusk until the fields are cleared, then planted, and he can have the pleasure of not planting for a while, but weeding and getting rid of rocks instead. Then between tending to the young plants, plus keeping the forthcoming rabbits, rats, aphids, beetles, moles, deer, and another hundred kinds of pests at bay, he keeps busy watering, always watering, or worrying about too much or too little rain, all the time praying to his gods for the harvest season to arrive ahead of the locust, so he can start getting up before dawn to do that. Then comes the storing of the harvest, be it grain, such as wheat and barley, or lentils, peas, and potatoes, or whatnot. Usually there’s no end of cleaning and sorting to be done, not to mention separating and screening the seed for the next year, plus keeping an eye on mice and insects that insist on their fair share. Did I mention drying the fruit, like making raisins out of grapes, or prunes out of plums, so they can be stored? If you’re lucky and the fungus didn’t hit too hard and the mice and weevils were thoughtful and left some, then there should be enough food for someone to distribute, making sure each family gets a fair share, only it’s never as much as they want. After all, it has to last until the next harvest. When it’s all said and done, someone has to organize the men, post guards and protect the stored food from the neighboring tribes who were always itching to get their hands on it, especially if they had a bad year. And there were always bad years. Four years later, and regardless of whether the harvest was good or bad, the land is so used up and exhausted, it won’t even grow rocks, besides no more trees or fuel nearby, so they have to move the fields to another spot and start all over. All in all, it’s a wonderful, carefree life, one where you don’t have to count your calories, but one where you have to bear the pain of herniated disks and inflammation due to worn out joints by the age of thirty. Plus, never a minute to spare.

“Compare that to our hunter gatherer who sleeps late, sends his wife and daughters out to the inlets at low tide with a basket to gather what’s there. An hour or two later he’s had his breakfast. And not just any breakfast, but the kind of breakfast few people in Europe can afford: fresh clams, mussels, boiled rock crabs, take your pick. Fresh everything including eggs, unless it’s smoked first, which provides variety and is often tastier. Then he steps outside his wigwam, looks up at the sky, stretches, and he’s so happy and full, he decides it’s time for a mid-morning nap. The women bring the firewood, always plentiful, because it’s from the branches that drop to the ground naturally, never from trees he chopped down, as that amounts to actual work and is something to be avoided. Or there’s driftwood, tons of that.

“Once or twice a month he and other adults go hunting for seals at the colony, and take the young boys along. The kids can play and gather eggs on the way there, then bring the baskets back on the way home. His main work is bringing the seal meat back as well as the skins. Hunting seals or other marine mammals is no problem, as they are so plentiful he has to be careful not to trip on them. Occasionally when he gets tired of seal meat, he goes inland, hunting for fox, or guanaco, which provides a change of pace, in addition to a different type of pelt, not to mention the challenge of the chase, which he thoroughly enjoys, similar to adding pepper and salt to your food and spicing it up. Even so, he only goes during good weather because it usually means staying out for a night or two.

“Or he decides to go fishing. Using a spear works well, or a bow, and both are fun things in which the kids can participate. Easy to do at low tide, since there’s so many fish flopping in a thousand different shallow pools that a blind person can feed an army. Using hooks made from bone is sometimes better at high tide, and either way, he always catches more than he’ll ever need. Did I forget the king crabs? From the rocks where I stood yesterday, I could see what appeared to be an army of millions, all marching in formation along the coastline, right up against the rocks and not more than three feet under water. Add that to the list of delicacies he could jump in and grab until his arms turned blue. All of it sustainable, by the way, since there were never enough people to be a meaningful drain on available resources. Then there’s the blacked-winged ground doves, or the steamer ducks, or bronze winged ducks and ruddy-headed geese. One day I’ll make goose using my grandfather’s recipe and you’ll sit there after dinner unable to move, ‘cause you ate too much, then dream about it for a week. I could go on, the list is never ending.

“Think of how free people were before agriculture, how much time they had. No plowing, no hoeing, no weeding, no watering, no worrying, or losing sleep about the locust or wild pigs eating the crops, the floods drowning it, the drought killing it, or the neighbors stealing it. Nothing. Just hunt and gather for a few hours, then spend the rest of the day and evenings grooming each other, or making babies, or watching the children play while telling jokes and laughing at the sometimes new, but mostly old glorified hunting stories, told and repeated around the same campfire by every generation since the first one.”

I could only smile. Antonio had parts of human social history all figured out. “I didn’t know we had king crab so close to our shoreline, or that many,” I managed to say.

“You do now, and you get to try some. I brought back a bag full. That’s our dinner tonight.”

“But what about man’s worst discovery, agriculture?” I asked. “I don’t see the connection. What does your theories on agriculture have anything to do with the tracks people made going through the estancia? People we suspect are trafficking drugs and making tracks where there should be none”

“Simple. Basically, nothing here happens by accident. Perhaps in other places it does, but not here. The Onas didn’t come here by accident and neither did the other native tribes. They came here because, in my opinion, they saw nothing to like in agriculture. They were smart. They preferred cold oysters, fat geese broiled over hot coals and king crab instead. Our suspected drug runners are here because there’s something that attracts them. And I don’t mean looking for what they lost. The drugs and men they lost the other day are probably factored into their business model anyway. All business men factor in a certain amount for loses, and the drug business, I suspect, is no different. Sure they would like to know what happened to their men and their product, but that’s not the reason they are here.

“What bothers me is those men getting lost in the first place,” I said. “Even dead, they looked salty, experienced, like they’ve done this before. I can’t figure them dying from exposure and somehow losing their backpacks along with everything else, without any sign of where the stuff went to, or who took it from them. They had the latest equipment, the best outdoor gear and there were no signs of foul play. Plus, there were no other tracks and I’m sure they were well armed. I can’t imagine them being there unless there is a very good reason.”

“You’re right. We need to find the real reason they’re here, and it’s not the food. I suspect it has to do with the geography of the place, and cutting through the estancia has something to do with it. Maybe in the morning we can go look and see if we can get an idea.

“When the police and I went to look,” I added “we got wet and nearly died from exposure ourselves, only we weren’t as well equipped as they were. Ten minutes of walking around between those bushes while slipping and sliding over the soft vegetation, and all we wanted to do was get back, take a hot shower and change into dry clothes.”

Antonio thought for a long minute while I tried to anticipate his thinking, knowing all the time it was hopeless. Getting mentally ahead of Antonio was a waste of time. Maybe María could do it, but I never could. And I wasn’t wrong.

“Well, a good idea that gets no praise at all, is the one-eyed needle,” he said, as if that one short sentence explained it all.

How could anyone have anticipated that?

And just like that, his eyes were twinkling again.

“To me, it changed the course of human history,” he added “every bit as much as the discovery of agriculture, only this time in a good way.”

I grinned. It was time for another good story. Two in a row. Not bad for an old buzzard, who would have been senile anywhere else, but not here. The climate, the sea air, the exercise, the good solid food, a loving wife, whatever, and probably a combination of all of it, added up: here, he was full of life. He was also full of stories, anecdotes, yarns, whoopers and fairytales, you name it, and I was eager to hear another one, especially if the story had a point. Never mind the hyperbole.

“A person that knows how to use one of those needles,” he declared, “can make clothes that are more waterproof than any modern fancy-pants alpine gear can ever be. If you use beaver pelts, for example, they are not only waterproof, but light, and warm. María is an expert at it, although I can do a pretty good job myself, only I’m out of practice and it takes me longer. If the jackets are made so they can be reversed, wearing one with the fur to the inside can roast a person, unless it’s twenty below. When it gets that cold, there’s nothing better.

“Then there’s the footwear. With a good pair of knee high moccasins a knowing person can walk around in any weather and no problem with getting the feet wet. They won’t, not if the seams are made a certain way. If the soles have fur, they become non-skid and leave no footprints, at least not any that can be seen, unless you know what to look for and are a very good tracker.

“If you wrap your horse’s hooves with some of that fur, then there’s no hoof prints either. An army can canter through this estancia and leave no more indication that a trout going upriver in muddy water. On the other hand, I’ve seen the footprints of those that carry drugs across here. They use army boots and make such a deep waffle imprint, one doesn’t have to look for them. Using moccasins, one can feel them in the dark, with your feet, they are so well defined. A blind man can follow them using his toes, not even looking at the ground.”

When he ended, I didn’t ask any questions. I figured Antonio was trying to tell me he had things well under control and for me not to worry.

Before long we finished our bread and coffee and he walked me to the jeep. As I was climbing aboard, he patted the door and said, “Keep her fueled. You never know when you might need her next,” and laughed.

I didn’t say a word, I was busy with my own thoughts, although what they were was hard to say ‒ they were confusing and I don’t recall. When I got home, I remember saying to myself “Well, that explains why the cops can’t find any foot prints, or hoof prints, or anything else.” And “rats, he’s having king crab all by himself.”