A story I submitted to a teacher friend at SMU was actually liked by a lot of the students. They said it was different and fresh, not the same old boy meets girl and they both die before getting married yarn. Here is one of them. I’ll post the other one later. Again, any feedback is appreciated.

m

~For the glory of it ~

“I’m glad you’re back,” I said

Antonio smiled. To look at him, one would think there was not a problem in the world, at least not any which concerned him. It even crossed my mind to think he was blind to them, while I noticed them all, including the smallest one. Now that we were alone, my intentions were to question him on the bag full of human ears he had given me to take to the police, and how it came into his possession, but I hesitated. I wasn’t sure I wanted to know, besides, I was in a hurry to get back home.

“I got back early this morning,” he explained. “I love traveling through the estancia at night. That’s my favorite time.”

“Hah!” I snorted. Traveling at night was impossible, I knew that. Traveling in daylight was bad enough. Tierra del Fuego was no park, there were no dedicated camp sites, no quaint little signs showing the trail to the snow-cone stand or the souvenir shop. There wasn’t any kind of a stand anywhere, or any shops, much less any kind of a trail. This land was the same as the Maker had originally made it, seemingly untouched since the beginnings of time, except by wind, rain and ice, the three mayor forces that shaped the land and everything on it, besides the occasional earthquakes. For a modern man like me, going out into the backcountry at any time was dangerous. To say the land here was raw and wild was an understatement, to believe that was a mistake, to travel at night was probably the worst mistake. At night, nobody could go ten feet past the edge of town without getting lost. I knew he was pulling my leg and I started to complain.

“It is my favorite time,” he said, interrupting me. “My horse does the walking and I do the thinking, or remembering, while talking to him, when there’s nobody else around. That horse was born here and knows how to get ‘round, plus he’s good company and a good listener. My grandfather and I used to go out a lot at nights. We did that all the time and in those days, nobody thought twice about it. Sometimes we used to be gone for days . . . on a condor hunt.

I looked at him again to see if he was serious.

“We did,” he continued, reading my mind, “although we never killed the bird or damaged it in any way. I think we were the original tree huggers” he said, laughing out loud, his eyes twinkling full of mischief. “We just plucked a tail feather and let him go, like good econuts. That’s what the Incas used to do.”

Talking to him for a few minutes had relaxed me, as it always did, and I wasn’t in a hurry to get back anymore.

We went to sit in his kitchen instead and he boiled water for coffee.

“I understand that your son Cris is now a reporter?” he asked.

As always, when Antonio asked a question, it wasn’t so much the question, but the intent. His questions were like verbal shovels, not only good for scrapping the surface, but also calculated to dig deep. Questions that kept me on my toes.

So I told him. “Yes, he’s now officially a reporter. He and his friends are. That’s their summer job and the best part is that they’re serious about it. Not just this sounds like fun and we’ll try it for a few days serious, but really serious. He asked for a camera and I gave him an old one of mine. Then four more school friends wanted to be included, so I got each a camera.”

Antonio nodded his approval.

“But that’s not all. Now he wants to be a famous reporter. They all do. For now, however, their job is to take pictures and write a small byline on what the picture is about, what it means, names and places, that sort of thing. So far we have published two of their pictures and a small article. I think the pictures are pretty good.”

Antonio leaned back in his chair and lit his pipe.

“What are the pictures about?” he asked.

“Mostly life around town. One was a picture of our two dogs playing with Poor Devil, our baby guanaco. The other one a picture of the whole town before a rainstorm, or a sandstorm, it’s hard to tell which. It looks abandoned, deserted like a ghost town, not a person in sight.”

“I can help them get a story along with a picture that is guaranteed to be published in any newspaper or magazine, including Nature or the National Geographic.”

I looked at him. Antonio was good at pulling my leg but this time he appeared to be in earnest. I asked myself what he might be plotting.

“I can help them trap a condor,” he said. He looked serious.

Now I knew he was kidding.

“I’m not kidding” he said, reading my mind again. “In the old days, the Incas trapped them all the time, same as the Mapuches, same as the native people here. I think it gave them something fun to do. I did it several times myself.

I looked at him, an expression of doubt in my face.

“When I was younger,” he added.

He had my attention.

Antonio looked at me and seeing I was actually listening and not trying to argue as usual, he continued.

“When we were kids, a gaucho called Martín that worked for my grandfather here at the estancia told us of going condor hunting as a young man with his native Fuegian friends. And the idea wasn’t to capture the bird and make money from it, or cause it harm in any way. It was done for the glory of it. Afterward, like I said, they plucked a feather for a memento and let it go. The person that actually did the capture got to keep that feather. I have several.

“I’m listening,” I said.

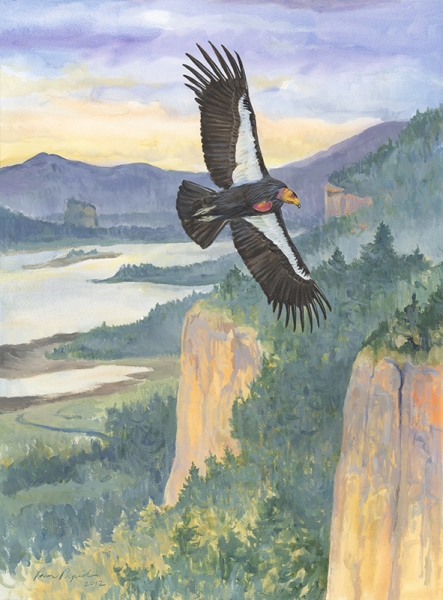

“In many Andean cultures, the condor has always been the symbol of the Andes, of the cordillera. The big bird is the icon of vigor and health. In Andean mythology, the condor is associated with the sun god, the lord and master of the sky.

“Sixty years ago, there were more condors,” continued Antonio, “many more. I’ve gone on puma hunts up in the mountains and have seen fifty condors flying at a time, making great big lazy circles way up in the sky. They’ve been known to go up to three miles, you know. That’s high. And they hardly beat their wings, they float instead, they glide easily, without effort, suspended light as a feather on the thermal currents. That’s why you hardly see any until the day warms up. Today, they’re still around, but sadly, not as many as before.

“A lot of the ranchers believe condors kill their sheep, especially lambs,” continued Antonio, “so they leave poisoned meat for them to feast on. The fact is that condors don’t kill anything. They are glorified vultures that mostly eat carrion. In any case, I never saw a condor kill anything bigger than a jackrabbit. Neither have my friends. Look at them, they don’t have the beak or claws to kill anything big. They are different than eagles, hawks or even owls, and are clumsy, even ungainly, when not up in the air. They are not designed to kill. Their beak is strong, but made to tear into things, not cut or slice, plus they don’t have talons, they have claws that are mostly blunt. On the other hand, if it’s dead and bloated, they love it: deer, guanaco, horse, fish, beached dolphins or whales, even mice and dogs, whatever. Then, they drop out of the sky like fat bricks, one by one, or in what might be called groups, or even clusters. That said, there is also no shortage of worthless condors, like in everything else. I’m referring to the ones that disgrace the species and smear their reputation. Those are the ones that steal hatchlings from a penguin’s nest, or eat the eggs of other birds. The time I saw one finish off a wounded jackrabbit, it beat it to death using its beak ‒ that was undignified and shameful.

“They nest up high, though, and if you want to catch one, we better go soon since it takes a few days just to get there. Seven thousand feet is about right for them, or higher. That’s why it has to be summer time. I don’t think I would take school kids up there in winter. It’s doable, but I don’t recommend it.

“Are you serious?” I asked.

“Of course,” he said. “For kids, it’s better than playing videos or spending time watching television. And if they don’t get one, it doesn’t matter. Either way they will never forget it. Several of the best condor hunts I ever went on, we never actually caught one, but we did get to see them up close, real close, including their nests.

“And how is it that one catches one?” I asked, doubtful of his every word.

“The old fashioned way” he said. “Really, the only way I know. Mainly, you go up the mountain and dig a hole big enough to climb in. After that, you get in and your friends cover the top of the hole with branches and grass. On top of the branches, they drop a dead goat, a guanaco or a sheep carcass, some kind of dead meat. Even a couple of big rabbits will do. In the old days, if you were an Inca, maybe the mutilated body of an enemy. And there were lots of those, ‘cause if you weren’t an Inca, you were certainly an enemy.

“The rest is easy, if you have patience, and mainly you wait for the bird. When he lands on top, you reach between the branches and grab a leg. With the other hand, you try to get a rope around the leg to hold him. Meantime, he’s flapping his wings furiously, mad as hell, while you’re busy screaming, yelling, calling your friends, who are hopefully close by and didn’t wander off to pee somewhere, so they can come to the rescue. I say rescue because at that point, it’s never too clear if you got him, or he’s got you. I’ve seen it go both ways. Best to have some friends run over and throw a blanket over the bird to quiet him down, that way nobody gets hurt. Once you got him secure, you select a feather, pluck it and let him loose. Sometimes, they lose a few tail feathers in the struggle anyway, so there’s plenty to go around. I imagine these days you pluck a feather, take a picture with your phone, and let him go. Simple.”

Antonio was smiling.

“Sounds easy,” I said.

Antonio laughed out loud. “If you come with us, I promise you, it will be the most difficult thing you have ever done or will ever do. From then on, your life, your every endeavor will appear trivial by comparison and you will live your days planning to go back so you can once more experience that rare moment of personal glory that was actually earned, the one that gave some meaning to your drab existence . . . as a modern, state-of-the-art, cutting-edge man.

I looked at him.

“As opposed to a traditional man from the Fuegian culture,” he added.

The way he said it made me frown. I knew he was poking fun at me, trying to rile me up, and I wasn’t going to allow him the satisfaction. “Which is the hard part?” I asked, struggling to remain unperturbed, although, and since we were speaking of feathers, unruffled might be a better word.

“Everything,” said Antonio. “Getting partway up there on horseback across flimsy, twisting mountain trails and narrow, slippery log bridges, without falling down a gorge and disappearing into the clouds below is no easy task, neither is climbing the rest of the way on foot to be near them, while toting enough supplies to last a few days. Then, there’s the digging a big hole into the rock-solid frozen ground and the silent wait. There’s also the lack of oxygen, the rain, the cold steady wind, sometimes sleet, or snow, but the hardest part is grabbing the bird’s leg without losing a hand. In short, everything.

When he finished, I just sat there looking at him quietly puffing his pipe.

“Up in the mountains is where I learned the difference between loneliness and being alone,” he added, after a long silent pause in which his tobacco smoke drifted over to me and fill my lungs with its intoxicating aroma. “Up there, even if there’s three of four people with you, everything is so big, so imposing, so utterly extreme, you are essentially alone, especially if it’s your turn to be under the branches waiting for a bird to land. Like many things, you have to experience it since it’s hard to explain.”

I looked at him.

“If you have to climb on foot from where you leave the horses, and it takes several days, who stays with the horses?” I asked.

“Nobody” he answered. “You tie the reigns around the saddle, slap the horses on the rump and they go back on their own. Like I said, they know the way around and especially the way home.”

“So you walk back?”

“Sure, but it’s all downhill.”

I thought about it.

“I forgot to mention about waiting with a rotten carcass a foot over your head. It might be freezing, but the smell of carrion doesn’t get any better with time.”

I couldn’t believe he had convinced me.

One thought on “For the Glory of it.”

Having seen these majestic creatures from up close, I can appreciate the thrill (and environmental conditions) of the wait, alas unfruitful for the narrator this time. True be said, I would not have the gumption to engage in this adventure but it makes for a good story. I always enjoy your writing.

Comments are closed.