I read a lot. In fact, I read a hundred and write one. Not that I time myself or keep track in any way, but I do read a lot. From time to time I luck out and run into a book worth mentioning, then I will write a small description and rate the book from 1 to 10, although, I doubt I’ll ever get carried away and go whole hog to 10. If your taste runs parallel to mine, it might be worth checking into. The following are not in any particular order.

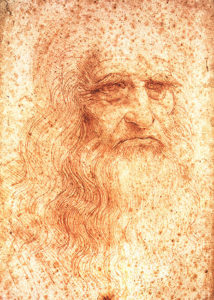

Leonardo de Vinci. A biography by Walter Isaacson

In a word: boring.

Yes, Leonardo is considered the world’s most creative genius to date and no doubt he has the two most famous paintings: the Mona Lisa and the Last Supper. That’s all fine, but who wants to sit through a blow by blow of how Leonardo spent hours and hours at the morgue dissecting cadavers until they were too far gone even for him? And yes, I get that left handed crosshatching was an innovative way to render subtle shades, but I don’t need to be told countless times.

Actually the book is boring, that’s not to say Leonardo’s life was. He was in fact a man way ahead of his time, in many cases, centuries ahead and stood at the crossroads of science and art. Some of his drawings, especially the cutaway views of the human hand, arm, lips, and especially of a human fetus, are the best ever rendered and had he done nothing else, he would have been famous for that, if he had bothered to have them published.

Leonardo questioned everything that interested him, and it seems everything interested him. Birds, human anatomy, weapons, flying machines, geology, botany, sculpture, colors and painting, lighting and shades of lighting, architecture . . . the list is long. Mix limitless creativity and imagination coupled with a God-given talent as well as a sometimes heretical point of view and you have the making of a Leonardo.

Sadly, this is not the book to tell it. I give it a 4 on my list from 1 to 10. And the four mostly for the effort.

mt

Links:

Embryo in the Womb (1511 -1512)

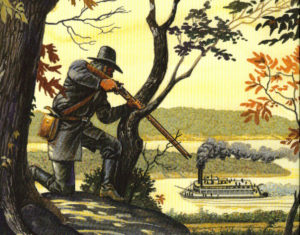

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court. A novel by Mark Twain – 1889

A masterful work by the master of sarcasm, caustic mockery, irony and parody.

A masterful work by the master of sarcasm, caustic mockery, irony and parody.

Nothing is safe in the world of King Arthur when it comes against the pen of Mark Twain: the government, the law, petrified opinions, superstition, the medieval Catholic Church, Merlin the magician, and any and all institutions, including that of slavery and chivalry, come under the hard scrutiny of the author and fail miserably.

Hank Morgan, a practical and knowledgeable Yankee engineer working at the Colt factory in Connecticut suffers a blow to the head and wakes up in the court of King author. He is immediately made a prisoner but in no time bounces back realizing he is the smartest man in the planet: 1300 years ahead of the rest. That’s when he sets out to modernize the country by building factories and schools. All hidden, however, and secretly working, so as not to arouse the enmity of the Church that grows fearful of his power. For a while he succeeds, but the Church is too much for him and eventually things catch up. Try as Hank might, in the end it turns out that education, justice, freedom to think, freedom to work and freedom from onerous taxation are no match for a dedicated church. Told with a very sharp and dry sense of humor, it is not only extremely entertaining but thought provoking as well.

A pleasure to read. An easy 8.5 on my scale from 1 to 10.

mt

Alaska by James Michener.

A friend of mine once told me that if Alaska was split in two, Texas would be the third largest state. Being from Texas, I naturally had to decide whether to be rankled or not, then decided to laugh instead: it was true. Alaska is big, really big, and in his book, Michener gives us the highpoints of America’s last frontier in an epic way: from the very beginnings to the modern age. And any one part of the book could have been a book by itself, starting with its unique geography and geology, and the slow shift in the Earths tectonic plates that gave rise to the land. Then comes the history of the first humans to live there, Russian ownership and subsequent sale to America, the gold rush, the huge salmon industry that developed, the pelt trade and the inevitable exploitation of the natives by the first captains and boat crews that went there, and much, much more.

A friend of mine once told me that if Alaska was split in two, Texas would be the third largest state. Being from Texas, I naturally had to decide whether to be rankled or not, then decided to laugh instead: it was true. Alaska is big, really big, and in his book, Michener gives us the highpoints of America’s last frontier in an epic way: from the very beginnings to the modern age. And any one part of the book could have been a book by itself, starting with its unique geography and geology, and the slow shift in the Earths tectonic plates that gave rise to the land. Then comes the history of the first humans to live there, Russian ownership and subsequent sale to America, the gold rush, the huge salmon industry that developed, the pelt trade and the inevitable exploitation of the natives by the first captains and boat crews that went there, and much, much more.

Along the way, we learn that for most of its modern history (16th century to present), Alaska had no viable government: a long way from Russia, with the Czars slow to make decisions on a territory they didn’t understand, plus, forever busy with more important matters closer to the Mother Land. After the sale to America, a long way from Washington as well, so that Alaska remained to fend for itself, like a distant unwanted stepchild, mostly forgotten by its new government. In fact, were it not for the otters and their valuable fur, Russia would not have been interested at all, and it was a miracle that America became interested, or came up with the money to purchase it, some newspapers at the time calling Alaska a “Polar Bear Garden,” and most senators considering Alaska an icy, barren waste, and most certainly a waste of their time and the taxpayers money. (At first it was named the Department of Alaska, then later renamed District of Alaska and finally, the Alaska Territory, before finally achieving proper statehood in 1959).

I enjoyed all of it, partly because it is so well told, but also because Michener manages to weave it all together in such a way that we follow the progress of several people and families through different countries and many generations: it’s not the usual way to tell a story, and he does it so well.

In this book we meet the dirtiest, scroungiest rascals, the blindest men imaginable, as far as vision for a future Alaska goes, true heroes, hardy frontiersmen, strong, resilient, exemplary women, as well as people who live to build and those who love to destroy—we meet them all. I give it a 7.8 in my scale from 1 to 10: classic Michener, highly recommended.

mt

Captains Courageous by Rudyard Kipling

A 1897 classic by a master.

From the very beginning the book captured me. This is the story of fifteen year old spoiled brat Harvey Cheyne who is accidentally washed overboard from a luxury ocean liner on the way to Europe. At first, I was sorry he got picked up, thinking instead the sharks should have go at him, then deciding that even the sharks didn’t deserve this rotten morsel. Let him sink to the bottom, I though, he’s crab meat, which would have shortened the book considerably. But luckily, Kipling thought different, so that eventually he gets rescued by the “We’re Here,” (what a great name for a fishing schooner) where all his fantastic tales of having his own horse drawn buggy, living in mansions, riding in his father’s private railroad car in addition to his princely allowance, mean nothing. Aboard the We’re Here life is simple, only not easy. Simple because fishing is all there is to do, other than eating on the run and sleeping in a hurry. Not easy, because this, after all, is the north Atlantic, so the work is cold, wet, hard, salty and long. And let’s not forget dangerous. Very dangerous. Basically, it’s work or go hungry, and so they work.

From the very beginning the book captured me. This is the story of fifteen year old spoiled brat Harvey Cheyne who is accidentally washed overboard from a luxury ocean liner on the way to Europe. At first, I was sorry he got picked up, thinking instead the sharks should have go at him, then deciding that even the sharks didn’t deserve this rotten morsel. Let him sink to the bottom, I though, he’s crab meat, which would have shortened the book considerably. But luckily, Kipling thought different, so that eventually he gets rescued by the “We’re Here,” (what a great name for a fishing schooner) where all his fantastic tales of having his own horse drawn buggy, living in mansions, riding in his father’s private railroad car in addition to his princely allowance, mean nothing. Aboard the We’re Here life is simple, only not easy. Simple because fishing is all there is to do, other than eating on the run and sleeping in a hurry. Not easy, because this, after all, is the north Atlantic, so the work is cold, wet, hard, salty and long. And let’s not forget dangerous. Very dangerous. Basically, it’s work or go hungry, and so they work.

Lucky for Harvey, the men aboard the We’re Here are good, salt-of-the-earth-fishermen, and he makes friends. After the inevitable bloody nose and rough handling by the captain (with good reason), Harvey gets in line, and soon enough he’s learning how to work, taking pride in the work he does, and valuing his new friendships: Harvey is actually changing and miracle of all miracles, for the better: he’s really human.

Intertwined with Harvey’s adventure of fishing the Great Banks of Newfoundland for an entire season, are stories of the cod fishing industry, the Boston whaling industry, and what steam and sailing ships were like in the 19th century.

I give it a strong 9 on my scale from 1 to 10, the highest rating so far. Then again, it’s Kipling we’re talking about.

mt

Born to Run by Christopher McDougall

A fun book to read and one that will upend a lot of the notions we have become comfortable in believing. The book is basically about the Tarahumaras Indians of northern Mexico, a tribe isolated in the deepest of canyons, Mexico’s Copper Canyon, and who love to run. So much so, they have perfected the ability to run hundreds of miles barefoot through open country without injury—and just for fun. Not only do they run, but they do it without modern footwear, without digestible calories, without electrolyte drinks and without experienced crews monitoring their vitals. The Tarahumaras have no nutritionist to help them, and were they to ask for a drink, they would ask for a beer. It made no sense.

A fun book to read and one that will upend a lot of the notions we have become comfortable in believing. The book is basically about the Tarahumaras Indians of northern Mexico, a tribe isolated in the deepest of canyons, Mexico’s Copper Canyon, and who love to run. So much so, they have perfected the ability to run hundreds of miles barefoot through open country without injury—and just for fun. Not only do they run, but they do it without modern footwear, without digestible calories, without electrolyte drinks and without experienced crews monitoring their vitals. The Tarahumaras have no nutritionist to help them, and were they to ask for a drink, they would ask for a beer. It made no sense.

The book has insights into modern medicine, as compared to old-time medicine, modern running, as compared to old-time running for the hell of it, and modern footwear, as compared to bare feet. It goes into the physiology and psychology of the runner, the philosophy of these Indians, their way of life and what makes them tic, or run. It’s fun to read, occasionally serious and hilarious at the same time, and always moving at a fast pace.

“How come my foot hurts?”

“Doctor: Because running is bad for you.”

“Why is running bad for me?”

“Doctor: Because it makes your foot hurt.”

Horses don’t get shin splints, wolves don’t wear icepacks on their knees and antelopes are not disabled with impact injuries. Then why me? McDougall asks himself. Since nobody has a ready answer for him, he goes looking for one. The problem: the ones that have the answers, are the Tarahumaras, and they aren’t talking.

Along the way, we learn a lot.

An easy 7.5 on my scale from 1 to 10

mt

Hondo. A classic story by Louis L’Amour.

Hondo Lane is a scout for the army in the Arizona territory, during the time Vittoro and his Apache warriors were  about to rise and cause problems for the settlers. Hondo, among other things, was good at staying alive, had lived with the Apaches for several years and knew their ways. He was strong, dessert wise, big on honor, and a sentimentalist—not a bad combination for an army scout. He also had a dog: a big mean mutt with a low warning growl when others approached that had to scrounge his own food and whose main job was saving Hondo’s bacon, time and again. The dog hardly ever got a kind word, but was nevertheless all about Hondo. I really got to like the dog.

about to rise and cause problems for the settlers. Hondo, among other things, was good at staying alive, had lived with the Apaches for several years and knew their ways. He was strong, dessert wise, big on honor, and a sentimentalist—not a bad combination for an army scout. He also had a dog: a big mean mutt with a low warning growl when others approached that had to scrounge his own food and whose main job was saving Hondo’s bacon, time and again. The dog hardly ever got a kind word, but was nevertheless all about Hondo. I really got to like the dog.

Then there is Angie, the young mother of a small child abandoned by her worthless husband and living alone in a remote Arizona ranch. From the very beginning sparks fly between the two, so there’s not much guessing whether or not they will eventually become a couple. The question is how, since Angie is still married. Luckily, Hondo unwittingly takes care of that.

Generally speaking, a good fun story to read, well written, with the flavor of the time and place: the sun is hot, the dessert dry and unforgiving, the Indians well led by Vittoro, and the army always fumbling, but not to the point of embarrassment. This is not a story with a grey line. Everything is pretty much black and white: the good guys really good, the bad guys evil, and the line clearly defined. I give it a 6.5 on my scale from 1 to 10.

mt

The Soul of the White Ant, by Eugène Marais (1872 – 1936)

My favorite book, and if you read my reviews, you’ll notice many under “My favorite book.” Get over it, I say. If you can’t handle that, stop reading and go back to watching Scooby-Doo, where the imaginings are all done for you. If you can handle it, read on . . .

My favorite book, and if you read my reviews, you’ll notice many under “My favorite book.” Get over it, I say. If you can’t handle that, stop reading and go back to watching Scooby-Doo, where the imaginings are all done for you. If you can handle it, read on . . .

Termites, as it turns out (to my surprise), are fascinating and a life studying them might be considered well spent. Mr. Marais, a poet, a naturalist and a lawyer, spent ten years on this endeavor, sometimes lying flat on his stomach, putting a little paint on a termite as it went down a hole, then waiting patiently for it to reappear hours later, thus being able to figure out how far they traveled to find water.

The book is full of fascinating facts on the life of termites, besides their complicated social structure. In his relaxed, somewhat rambling stile, Mr. Marais tells the results of countless hours of observations with great insight, explaining how a termitary tower begins, the psyche of the termite, as well as their way of life, and much more: the explanations are detailed, colorful and fun.

Since Termites don’t live in a vacuum, he makes comparison’s to other creatures, both insect and animal, while describing the land around the termite mound and its many interrelations, besides the similarities or differences to these creatures: bees, ants, glow worms, tok-tokkies, and centipedes are mentioned, as well as animals like the kudus, penguins, giraffes, baboons and weaver birds, to name a few, helping to make the understanding of what he’s writing about easy in addition to comprehensive. Here’s an excerpt:

“Let us now observe another insect, our dear little tok-tokkie beetle, which will take us a good way along the path we must travel, and will greatly help to explain the secret to us. If you wish to learn to know the tok-tokkie really well and to learn to talk his language, you must tame him. He must become so used to your presence that he never alters his behaviour by suddenly becoming aware of being observed. He is very easy to tame, at least the greybellied one is, and learns to know his master and love him – you know the one I mean, the smooth little fellow with pale legs, not the rough-backed one. What South-African child has never seen the tok-tokkie and heard him make his knock? Your eye suddenly falls on him in the road or beside it. If he does not get a fright and fall down dead with stiff legs – as dead as the deadest tok-tokkie which ever lived – then you see him knock, and of course hear him, too. He looks round for some hard object, a piece of earth or a stone, and knocks against it with the last segment of his body – three, four, four, three! This is his Morse Code. He then listens for a moment or two, turning rapidly in many directions. His behaviour is ridiculously human. His whole body becomes an animated question mark. You can almost hear him saying: I’m positive I heard her knock! Where can she be? There, I hear it again!’ He answers with three hard knocks, and then he betakes himself off in great haste and runs a yard or two. He then repeats the signal in order to get a further true direction, and so he continues until at last he arrives at his loved one’s side. If you study the behaviour of many tok-tokkies during the mating season, you will occasionally have to follow one for an incredible distance in the direction of the answering signal. He can hear the signal over a distance which makes the sound absolutely imperceptible to the human ear. It is at this stage that he begins to rouse the interest of the psychologist. We study him at closer quarters. Again we find under the microscope no sign of an ear, nor complex or nerve which takes the place of an organ of hearing. But in spite of this we still think of the behaviour of the tok-tokkie in terms of sound and hearing!”

Wonderful. Who can resist? I give it an 8.5 (out of 10).

Historical note: Mr. Marais, born in Pretoria, South Africa, preferred to write in Afrikaans. In a classic case of unbridled plagiarism, Nobel Laureate Maurice Maeterlinck published the Soul of the White Ant in English as an entomological book, claiming it as his own, with no mention of Mr. Marais.

mt

The Man Who Counted by Malba Tahan.

Meet a man that counts everything: trees on the road, sheep in a flock, bees in a swarm, branches in a tree, birds in the sky, ants: you name it, he counts it. The man who counted is not only a good story teller, but a good traveling companion. On vacation and on the road to Bagdad in a camel, he tells the author about his life and travels. Along the road the two men become friends and the man who counted solves all problems, both real and imagined, using logic and mathematics.

Meet a man that counts everything: trees on the road, sheep in a flock, bees in a swarm, branches in a tree, birds in the sky, ants: you name it, he counts it. The man who counted is not only a good story teller, but a good traveling companion. On vacation and on the road to Bagdad in a camel, he tells the author about his life and travels. Along the road the two men become friends and the man who counted solves all problems, both real and imagined, using logic and mathematics.

A wonderful book, with great stories and easy to read. Original and totally different. I give it a 6.5.

mt

Jack Hinson’s One-Man War

A carefully researched biography of Jack Hinson (1807 – 1874) and his one-man war of revenge against Grant’s army.

From being a disinterested party, neither pro Union nor pro Confederacy, Mr. Hinson, a wealthy plantation owner minding his own business while living and farming in Steward County, Tennessee, turns ruthless sniper. And from my point of view, with good reason: two soldiers in Grant’s army kill two of Mr. Hinson young boys in brutal fashion, taking the severed heads to his plantation, Bubbling Springs, then setting the heads on the gate posts in front of the entire family.

There’s a lot to this book: from the basic tale of a savvy plantation owner, wise in the ways of living and fighting alone, familiar with the country he’s in, and with a powerful reason to take action, to the long term consequences of a brutal and unnecessary act of violence against a person’s family. All this against the backdrop of the civil war, with both armies clashing, with spies acting for both sides and army patrols as well as snipers possible at every turn.

There’s a lot to this book: from the basic tale of a savvy plantation owner, wise in the ways of living and fighting alone, familiar with the country he’s in, and with a powerful reason to take action, to the long term consequences of a brutal and unnecessary act of violence against a person’s family. All this against the backdrop of the civil war, with both armies clashing, with spies acting for both sides and army patrols as well as snipers possible at every turn.

What I liked most about the book was that it’s not told from above looking down at the action, but from right there, at a personal level, as if looking at the action in slow motion through a magnifying glass, fly in the wall style. In the end, it’s not what one army does to another army, but more what a lieutenant and a sergeant do to a man’s family, and what that man decides to do about it: Jack Hinson may be a church going family man, but he’s not one to be pushed beyond a certain point, and this was the point.

A little slow at times, especially if one is ready for the action to begin and Jack is still deciding where to get his sniper’s rifle made, but that was probably me being impatient. Through the telling, and aside from all the shooting, fighting, and dying, there are beautiful descriptions of plantation life, the countryside (Between-The-Rivers region of Tennessee and Kentucky), the work of slaves, tobacco farming, river crossings, friendships, love of life and family, so much so, one gets a good feel for the time and place, not necessarily the case in most other civil war books I’ve read. I give it a well-deserved 8.

mt

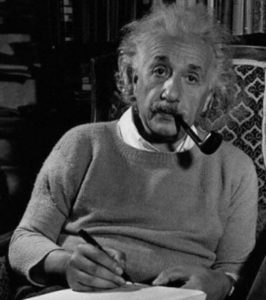

Einstein by Walter Isaacson.

If you like biographies, then this is a book for you: a fairly comprehensive telling of the man in question (Einstein: 1879 – 1955) that not only captures the essence of the man, but the life and times he lived in, as well. And what times. Being Jewish in Europe in the days leading up to WWI was not easy, but Einstein somehow kept moving, kept working, and kept his balance. Also, all the well-known anecdotes are in the book: how he could not find a job (mainly because when asked about his religious affiliations, he would write “none”), how he was a poor student, how he traded a Nobel Prize in the future for a divorce now, and how he was prone to daydreaming. That said, my favorite part of the book is to realize that when he published his most famous papers on relativity and special relativity, the bibliography was nonexistent: it was all original thought. Daydreaming for some, perhaps, working out universal truths for others. I give it a solid 7 (from 1 – 10). Loved the book for being thorough and at the same time, not overly so. I also loved to realize what a complicated person Einstein really was, and I was continually surprised at the people going in and out of his life: Niels Bohr, Marie Curie, Schrödinger, Heisenberg, Max Plank . . . the list is long and one wonders how he kept track of it all.

If you like biographies, then this is a book for you: a fairly comprehensive telling of the man in question (Einstein: 1879 – 1955) that not only captures the essence of the man, but the life and times he lived in, as well. And what times. Being Jewish in Europe in the days leading up to WWI was not easy, but Einstein somehow kept moving, kept working, and kept his balance. Also, all the well-known anecdotes are in the book: how he could not find a job (mainly because when asked about his religious affiliations, he would write “none”), how he was a poor student, how he traded a Nobel Prize in the future for a divorce now, and how he was prone to daydreaming. That said, my favorite part of the book is to realize that when he published his most famous papers on relativity and special relativity, the bibliography was nonexistent: it was all original thought. Daydreaming for some, perhaps, working out universal truths for others. I give it a solid 7 (from 1 – 10). Loved the book for being thorough and at the same time, not overly so. I also loved to realize what a complicated person Einstein really was, and I was continually surprised at the people going in and out of his life: Niels Bohr, Marie Curie, Schrödinger, Heisenberg, Max Plank . . . the list is long and one wonders how he kept track of it all.

mt

Turn Right at Machu Pichu by Mark Adams.

Rating: 8 (6 + 2 for humor= 8). Mark Adams goes to Peru, finds a guide (who deserves a book of his own) and rediscovers the old trails first blazed by Hiram Bingham, according to some, the original Indiana Jones. In the process, he trains to walk long distances at altitude, to climb, prepares for extended forays away from the Hilton, tells us about the Incas, the Andes, the wonderful Peruvians, and what made him think of this in the first place.

Rating: 8 (6 + 2 for humor= 8). Mark Adams goes to Peru, finds a guide (who deserves a book of his own) and rediscovers the old trails first blazed by Hiram Bingham, according to some, the original Indiana Jones. In the process, he trains to walk long distances at altitude, to climb, prepares for extended forays away from the Hilton, tells us about the Incas, the Andes, the wonderful Peruvians, and what made him think of this in the first place.

mt

The Martian by Andy Weir.

A well-written roller coaster ride of a story: astronaut Mark Watney is left behind on Mars. It was an accident, the first of hundreds perhaps, and so many that somewhere along the way I lost track. Mark, a botanist and mechanical engineer finds a solution to all of them using duct tape, bailing wire and good ol’ human ingenuity, besides luck—lots of that. Using the billions of dollars’ worth of tools and equipment abandoned on Mars, along with the help of NASA, the Chinese space agency, and eventually the members of his crew that are safely riding their spaceship back to earth, he figures out how to solve each and every problem he encounters; all of them life threatening. Food, water, air to breathe, being the least of them. And it’s not the laws of physics or chemistry that cause him grief, it’s Murphy’s laws, of which there is an ample supply. Evidently Nasa never once thought that Mr. Murphy would be alive and well in Mars: everything that can go wrong does, and at the worst possible moment. We know he eventually survives and gets a ride back home, which takes some of the mystery out of the story, but it’s nevertheless well written and funny, at times hilarious, although probably not intentionally so. I found it long, however and put the book down several times thinking “this is it, I can’t bear another disaster,” but curiosity got the better of me and soon I was reading again.

A well-written roller coaster ride of a story: astronaut Mark Watney is left behind on Mars. It was an accident, the first of hundreds perhaps, and so many that somewhere along the way I lost track. Mark, a botanist and mechanical engineer finds a solution to all of them using duct tape, bailing wire and good ol’ human ingenuity, besides luck—lots of that. Using the billions of dollars’ worth of tools and equipment abandoned on Mars, along with the help of NASA, the Chinese space agency, and eventually the members of his crew that are safely riding their spaceship back to earth, he figures out how to solve each and every problem he encounters; all of them life threatening. Food, water, air to breathe, being the least of them. And it’s not the laws of physics or chemistry that cause him grief, it’s Murphy’s laws, of which there is an ample supply. Evidently Nasa never once thought that Mr. Murphy would be alive and well in Mars: everything that can go wrong does, and at the worst possible moment. We know he eventually survives and gets a ride back home, which takes some of the mystery out of the story, but it’s nevertheless well written and funny, at times hilarious, although probably not intentionally so. I found it long, however and put the book down several times thinking “this is it, I can’t bear another disaster,” but curiosity got the better of me and soon I was reading again.

Along the way the reader gets a good sense of the difficulties of deep space travel, the seemingly impossible task of making Mars human-friendly someday, as well as the bureaucracy at Nasa, and a million other things one normally takes for granted here on Earth. I give it a 6.0 rating: a good read, if somewhat long, unless you are all about science fiction.

mt