“Are We Not Men? We Are Devo!” Robinson Jeffers and the Social and Biological Devolution of Humanity

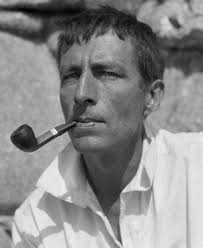

Because Robinson Jeffers’ physical body has not been with us for a long time, one may assume that he has little of a specific nature to tell us about society in the year 2006. But Jeffers’ world view—actually not just world view but cosmic view–extends from the birth of the stars to the death of the universe. It is based not on human institutions but on energy and the scientific principles that govern it. If we look at our life from this perspective, Jeffers always has something new to tell us.

Robinson Jeffers sees humanity as trapped by its animalistic instincts and appetites, doomed by what can be seen on the level of the single organism as a reasonable desire for self-preservation but which leads on the level of the species to destructive behavior toward other humans and the annihilation of other forms of life (e.g. “Passenger Pigeons [CP III 435-437]). Jeffers says that in the distant past, such activity was merely regrettable (“Original Sin”[CP III 203-204]), but in the past century the sheer number of people, augmented by the tools generated by our thinking ability, now threaten the existence of all life on the planet. Jeffers also has two main further responses to this development, one a rather forlorn hope, the other a consolation. The hope is that humanity could somehow recognize that its value lies not in prideful self-aggrandizement but in the understanding that it is only part of a great energy exchange which we call the universe. Then we could be content with “less,” which is actually more in terms of peace. The consolation is that the universe is running toward an inevitable end (in scientific terms, the resolution of the Second Law of Thermodynamics, “heat loss and death”), and the failures of the human race are simply part of that process. Jeffers, particularly in the poems written during the last two decades of his life (a period marked by World War Two and the unleashing of the atomic energy which brought that slaughter to an end) moves between lashing humanity for its stupidity and turning his gaze to the stars, which remind him of both the grandness of existence and its conclusion.

The human portion of this great flux disappoints Jeffers, but he was also a seeker after truth and therefore a scientist. Science describes the progress of creatures on this planet as evolution, the changing of life forms through what are at first random mutations, then natural selections which adapt to existing conditions better than other mutations, which die out. The most important word in the last sentence is “describes.” That’s what science does; it has no values other than factual verification and rational explanation of previously puzzling phenomena. As complete human beings possessing more than facts, we may decry the pollution of the environment, global warming, and the disappearance of other forms of life, but from a scientific viewpoint, our interference with previously established natural processes is just part of the evolutionary deal. Jeffers would say that the planet is going to die anyway; human activity will simply speed the process by wiping out carbon based organisms a few million years before the time that the biologists and geologists of the nineteenth century expected.

In recent years, the term “devolution” has been used to identify those changes which are destructive to the mindset or fantasy about the earth which we choose to have. Devolution means change “for the worse” in biological forms brought on by modern society. But the term “devolution” has no scientific meaning. The loss or drastic change of a widespread form of life might be thought of as devolution, to wit: in the southeastern part of the United States, the population of many species of frogs has declined alarmingly. We have a tendency to blame ourselves for all our problems, so at first observers speculated that the frogs might be dying because of pollutants we place in the water, air, or vegetation. But the most recent explanation of this phenomenon is that the frogs are victims of a virus to which they have no resistance. Unless the proliferation of the virus can be traced to human activity, we are off the hook on this one. Although this is very bad news for frog fans and the frogs themselves, this is just another change in the ongoing existence of the earth. Devolution is just evolution that we as human beings don’t like.

One way to describe the human part of evolution that we don’t like is atavism, a reversion to a previous evolutionary form, like Buck, the dog in Jack London’s The Call of the Wild, who begins life as a domesticated pet, loses his owner in the Klondike gold rush and becomes part of a pack of wolves, stripping off his veneer of traits acquired through contact with humanity and reverting to older species behavior. In human terms, people in a lynch mob are an example of such a reversion. I don’t think that Jeffers ever used the word “atavism” with regard to humanity, because to revert to an older type of behavior means that an individual must have progressed from that behavior. Jeffers thought that we are the same yahoos who grunted and cheered when they roasted that wooly mammoth in “Original Sin.” We have learned to flay the creature’s hide and wear it ourselves, but at bottom we are no better than dawnman (or person). To his credit, Jeffers includes himself in that group (“Fire on the Hills” [CP II 173]), recognizing that he also is human and subject to impulses that on reflection he does not find admirable.

The title of this paper is a quotation from the satiric rock group Devo, which had its day about twenty years ago. The members of Devo dressed uniformly in jump suits or paratrooper boots, black pants, blousy red velour shirts, and sunglasses. The crowning feature of this getup was a red plastic helmet that looked like a flower pot turned upside down atop a close cropped noggin. The group did not appear to have a lead singer or spokesman because they sang in unison and took turns talking when not performing. They played their instruments with robotic movements and drone-like sounds, accompanied with jerky dance steps that resembled the gyrations of puppets. All this was quite funny, and their music had a zany appeal. They did a reasonably good version of the Rolling Stones’ “Satisfaction.” The full title of this song is “I Can’t Get No Satisfaction,” which means that the song is really about frustration. This condition perfectly fit Devo, who looked like Pinocchios who would never get a chance to be real live boys. Are We Not Men? We Are Devo! is the title of one of their albums. That statement suggested that the answer to the ancient question, “what is a man?” could now be answered by saying that humanity, with its uncomfortable and confusing mix of instincts and reason, compulsion and freedom, had by the late twentieth century “devolved” into a state rather like that of an insect, which gets through life much more easily than we do because it is a set of programmed responses to stimuli. These responses are wrapped in a package of protein and carbon. Devo’s music is designed, tongue in cheek, to appeal to such an entity.

Aldous Huxley made the same suggestion in Brave New World; in the future, life will be simpler because we will have become like machines—those often unpleasant emotions, that perplexing freedom, will have been programmed out and “good chemicals” (a concept that Kurt Vonnegut also embraced) will lift us over the rough spots. In Huxley’s novel, the Savage, isolated from modern society and unable to adapt to it, found his free will such a burden that he killed himself.

Critics debate whether Huxley intended his book as a prophecy or a warning, but over seventy years after its publication and over forty years after Jeffers’ death, one point is clear. As George Allen used to say, “The future is now.” He meant that one must seize the day, but the statement also means that what once was predicted or feared is now everyday life. Although we spend an amount equal to the gross national product of many countries in the war on illegal drugs, the legal ones do just as much damage to our humanity. It’s a Prozac world as millions flee the pressure of our greed-driven reality for the solace of chemical tranquility. Devo’s music, originally intended as an extended joke, helped to spawn a new division of music called techno-rock. Although much of our popular music since the introduction of electric instruments (The basic musical instrument of the twentieth century, the electric guitar, appeared in 1938; the electric bass was added in 1959; the synthesizer in 1965.) can be said to have been created through the use of machines, techno-rock has such a mechanical sound that it seems to have been written not only by but for machines.

Jeffers had nothing to say about this development, of course. He never saw a computer or heard the sounds of a synthesizer, which is a machine which generates electro-magnetic signals on frequencies audible to human beings. But Jeffers did leave some signs behind which point us in the direction of these changes. Fire is of course one of the most familiar features of Jeffers’ work, sometimes appearing as a natural event, as in Tamar where it acts as it often does in nature as both a destroyer and a cleanser. Jinny, who accidentally sets the fire which destroys the Cauldwell house with a candle, refers repeatedly to that candle as “little star” (CP I 31) thus linking the ordinary flames which we humans see with another of Jeffers’ meanings for fire, the unimaginably dense energy which fuels the distant celestial furnaces and which, as the “older fountain” (also called in “Roan Stallion,” “fountain of lightning” [CP I 195]), is the source of all life, both the graceful gull and the fluffy bunny. And at the conclusion of “Roan Stallion,” California’s brain activity is described as being like stars: “Each separate nerve-cell of her brain flaming the stars fell from their places/ Crying in her mind” (CP I 198). Fire appears as a metaphor for love and sexual passion in Jeffers’s poetry as well. “Divinely Superfluous Beauty” says “The incredible beauty of joy/ Stars with fire the joining of lips” (CP I 4).

But—perhaps that fire is not a metaphor but an event. On a dry day, two people wearing shoes with insulating soles shake hands and feel the sting of a spark. Those lucky enough to kiss under such conditions will also generate electricity. Jeffers refers directly to this special sort of fire energy in the Prelude to The Women at Point Sur in which a thunderstorm releases the energy in the oil storage tanks at Monterey. That energy Jeffers describes as “straining” to get out, to change its form, to find a new outlet:

Always the strain, the straining flesh, who feels what God feels

Knows the straining flesh, the aching desires,

The enormous water straining its bounds, the electric

Strain in the cloud. The strain of the oil in the oil-tanks

At Monterey aching to burn, the strain of the spinning

Demons that make an atom, straining to fly asunder

Straining to rest at the center,

The strain in the skull, blind strains, force and counterforce,

Nothing prevails . . . (CP I 144)

In the poem, the pent-up energy finds release through a lightning strike as one of the tanks explodes. Unlike the trapped, long-lived energy in Jeffers’ beloved stones and boulders, the energy we call electricity is volatile, restless, seeking an outlet, anxious to find a new path, take a new form. It is the form of energy most like us—active, protean, Faustian, unfulfilled even after reaching a new destination, constantly changing and without peace.

I offer this anecdote in order to introduce a term I will use during the rest of this presentation. Twenty years ago I was President of the Denton, Texas chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union. I am again, having been called back like Cincinnatus from the plow, but that’s another story. Our meetings were open to all and always attended by David Lawhon, a high school student and son of a professor. David asked if I would speak about the A.C.L.U. to his Government (whoops, Political Science, although there is no such thing as Political Science) class at Denton High School. After receiving a formal request from the teachers to talk to two classes meeting together for the purpose of hearing me, I went to the school. First I showed them a brief video segment from 20/20 about the organization (I was hip enough to realize that you can’t just show up and talk, you gotta do something visual.), then explained its history, mission and activities and asked for questions. There were twenty five “students” in the room—the term carries quotation marks because a student studies. A colleague of mine on the first day of class used to say, “You are my enrollees. We shall see whether you become students.” For fifty minutes this is what I got from all twenty five people. [Do a take—slack jawed, mindless immobility.] The teachers asked a few questions; then the loudspeaker in the room blasted in with information about the next day’s schedule. The bell rang. The “students” rose, startling me—I thought I was viewing an elaborate trompe l’oeil painting, or perhaps I had perhaps been in the midst of one of those highly realistic sculpture groups. There’s one in Seattle at a bus stop that confuses actual travelers. The students shuffled away to their cars.

You can’t really blame them, though; they had been reduced to bovine passivity and zombie-like thousand yard stares by twelve years of an “educational” system which had destroyed the natural curiosity of childhood and replaced it with the socialization (read: emotional bludgeoning) needed for late twentieth century society. “Bovine” is not fair to animals, though. Cows do move. Do as you are told. Go to school, go to the mall, go to war. At the next meeting of the A.C.L.U. board, the members asked me how my visit to the high school had gone. I said, “Maybe David can judge the session better than I. My reaction is ‘The horror! The horror!’”

I am constructing an anatomy of horror based on the old Latinate description of the types of sentences. There would be simple horror (I guess the example above fits that.), compound horror, complex horror, and compound-complex horror. I haven’t been able to determine the qualities of all these, but I have nailed down interrogative horror. This is the horror one encounters when trying to get an answer to a question from another human being. Here are some examples:

–When I am in San Francisco, I always eat at the Tokyo Sukiyaki restaurant, located on the second floor of a building at Fisherman’s Wharf which overlooks the north bay and Golden Gate Bridge. After an enjoyable meal, I stretch this experience for another hour with a pot of tea, centering my soul and making contact with the spirit of my grandmother, who suggested that we eat at this place the first time I came to San Francisco in 1957.

In 2002 I went to Fisherman’s Wharf but couldn’t find the place. I asked at various businesses but most people could not help me. One fellow said that he knew where it was, but the place he directed me to turned out to be a sushi bar. (This might be complex horror—you get what you think is an answer, but it turns out that your respondent has accessed the general category “Japanese food” and thinks that all restaurants which serve such cuisine are the same.) The people at that place didn’t know where the Tokyo Sukiyaki was, although they were in the same line of work, as it were.

I figured that what I needed was a phone book. None of the businesses had one, and the few pay phones in the area had either been stripped of their books or never had one. Pay phones are becoming rara avis anyway, because everybody has a cell phone, a development which has a direct bearing on my conclusion. I went to the Travelers Information Center, certain that they would have a phone book. Nope. Finally the clerk at a knock-off jewelry store said, “Why don’t you call 411?” I hate telephones of all kinds (another story), so this solution had not occurred to me. As I left the store, the clerk shot at me in a surly fashion, “You owe me seventy five cents.” This is part of interrogative horror. The person asked the question is angry that their day has been interrupted by someone too fogbound to know how to get an answer without disturbing them.

The 411 person said there was no listing for Tokyo Sukiyaki. Out of business. In my wanderings, I found its old location now occupied by an In and Out Burger.

–Second example. I wanted to see Brian Wilson, who was performing at a new auditorium called the Nokia Nextstage Theater (Note that this venue is bankrolled by a telecommunications company.) in Grand Prairie, a town thirty miles away from my home. I decided to ask the students in my classes where the theater was. I said, “I know it’s at the intersection of Belt Line and I-30. My question is, which quadrant of that intersection? Which way do I turn when I get there?” Puzzled looks, no doubt triggered by the use of the word “quadrant.” There were at least six students in each of three classes who had actually visited the theater. Eighteen people. None could remember where it was. After some head scratching, from all three classes I got, “Look it up on the internet.” I responded with some heat, “I’m sorry. It was foolish of me to ask a flesh and blood person who has actually been there where the theater is when I could boot up a machine and ask it.”

But, you may say, consider the folks of whom you asked these questions. Commercial churls and students at a state university, notoriously vapid populations. Consider this, then. I’ve always thought that one of the advantages of working at a university is that you can quickly find the answers to puzzling questions. Pick the brains of your colleagues. A community of scholars. Third example: I was writing an article in which I mentioned Jacqueline Susann and was stopped by the spelling of her last name. I found two other English teachers in the hall. “Do you know whether Jackie Susann’s name has two or three “s”s? One or two “n”s?” My next door neighbor gave me a look that said, “Why must I interrupt my research to deal with this dunce?” She went into her office, I heard a keyboard clatter, and she returned with the right answer.

I had offended by asking a stupid question, i.e., one the answer to which could be obtained from the internet. What’s the matter with you, Baird? Anyone who has reached the age of reason (That’s a laugh, too.) during the last twenty years regards the world as only a keystroke away. Why remember anything? Why make the effort to store away something in one’s brain, when all knowledge is instantly available? Or rather I should say, all information is instantly available. I wonder if younger people know things in the same way that older people do. As a child, I did mathematical exercises filling out legal-size sheets with multiplication tables. Why memorize the product of five times eight? Don’t you have a calculator in your cell phone? (Note—in the original version of this essay, that sentence read, “Don’t you have a calculator in your wrist watch?” That’s laughable because I have since learned that today’s youngsters no longer wear wrist watches; if they need to know the time, they consult the ubiquitous, life-conferring cell phone.)

Furthermore, what do you do when you need a larger context? Suppose I had said to the 411 person. “So Tokyo Sukiyaki is gone, huh? Then give me the name, address, and phone number of every Japanese restaurant in San Francisco.” 411 is not programmed to respond in that area. So maybe that big fat phone book still has a place in this world.

My fourth example of interrogative horror is the worst of all and brings us back to Jeffers. I have to pass out a sheet of rules for classroom behavior to my students, one of which of course tells them to turn off cell phones, pagers, blackberries, p.d.a.’s, etc. This sheet used to be titled “Things Your Mother May Have Taught You and You May Have Forgotten.” That title was designed to remind students that manners are learned at home. Now I realize that mother was not at home to teach the current crop of youngsters anything; she was working at her job in order to buy an SUV and an X-Box for the children. So there is nothing to “remind” them of, I have to tell them how to treat others with respect. While teaching my class in Bob Dylan this semester, I played several folk songs to show the musical background from which the singer emerged (“Tom Dooley,” “Pal of Mine,” “Barbara Allen” and “Going Down Slow”). Because all of these songs are about death, students complained in their papers that the songs were “depressing.” I think that no effective work of art is depressing because one human being has touched another, but they weren’t ready for that idea yet, so I pointed out that all kinds of art have as their central theme death because it is a dramatic event that all of us must face. I believe that there are at least two sides to every issue. Death is a terrible thing, but it gives definition to life. I asked if they could see any positive side to death. Silence. I tried another way to get at it. Why do we fear death? Because we don’t know what lies beyond, someone offered. Okay, a start, but is there anything more motivational than that? I changed the terms to hatred of death rather than fear. More silence. They appeared not to have a clue, so finally I answered my own question, “I fear death because I love life. I have to die some day. Dammit, I hate that.” Even Jeffers, whose search for truth and unblinking examination of history and society led him to some very dark places, nonetheless, in poems like “Birds,”(CP I 108) “O Lovely Rock,” (CP II 546-547) and “Their Beauty Has More Meaning ” (CP III 119) finds himself suddenly and unexpectedly energized by the experience of life.

Thirty seven people looked as if I had slapped them. It apparently had never occurred to them that they enjoyed living.

When I gained some perspective on the incident, I realized that this response was my fault. My classroom regulations had deprived them of their minds. Without cell phones, without pagers, without blackberries, without p.d.a.’s, without—God help us—the internet—how can one know? I resisted telling them to go home and Google “death” for some way to begin. “Aw, goll-ee, I got twenty five million hits! I can’t go through all those.”

In 1970, there was an article in Life which described a robot which had limited intelligence. The robot consisted of a wheeled cart, a computer, a television camera, and a servo arm. One could, for example, tell the robot, “Go into the next room, pick up the cup on the table, and bring it here.” The robot could do this, although it took about forty five minutes. The reporter asked the inventor, “Doesn’t it bother you a little that you are giving intelligence to a machine?” The reply: “No. The robot is a computer made of metal. We are computers made of meat.”

It is easy for us to look forward, into the dissolving void that lies beyond death. Thinking of Una, Jeffers writes in “The Shears,” “death comes and plucks us; we become part of the living earth / And wind and water we so loved. We are they” (CP III 412). But Jeffers also looks back at the flux which precedes existence: “But as for me,/ I have heard the summer dust crying to be born/ As much as ever flesh cried to be quiet” (CP I “Cawdor” 513). That which must be born is ever seeking a way into existence—the strain, the strain. The last two centuries were first called the Age of Steel, then the Age of Oil, now the Age of the Atom. But they might just as easily have been called the Age of Electricity.

Electricity is glad we found it. Jeffers tells us that we are electricity. He notes that diffuse energy strives to find a form, to be born. He shows us the restless energy of electricity, probing, exploding, finding new homes and new pathways. He shows us bored humanity, eagerly attracted by the next vulgarity. We have constructed huge artificial waterfalls (hydro-electric dams) in order to supply ourselves with more of this energy to which we are addicted. Electrical power is so ubiquitous that we only notice it when it is absent. Checking into my motel room two nights ago, I was angered to find only two wall outlets, one inaccessible, the other loaded. How was I to plug in my laptop? Like Jeffers in “Fire on the Hills,” I too must painfully admit my shortcomings. We ourselves, trapped electricity, have become the meat, the protein portion of a vast electrical circuit to which we return at every opportunity as to a renewing fountain. It is our God. We can now understand machines better than we can people. Snugly secure in our electronic cocoons, the outside world concerns us little. Are we not men? We are devo!”

Jim Baird

University of North Texas

Work Cited

Jeffers, Robinson. The Collected Poetry of Robinson Jeffers. Five Volumes.

Edited by Tim Hunt. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1988-2001.